But IMN panel says that’s something to watch in the next 12-24 months

By Murray W. Wolf

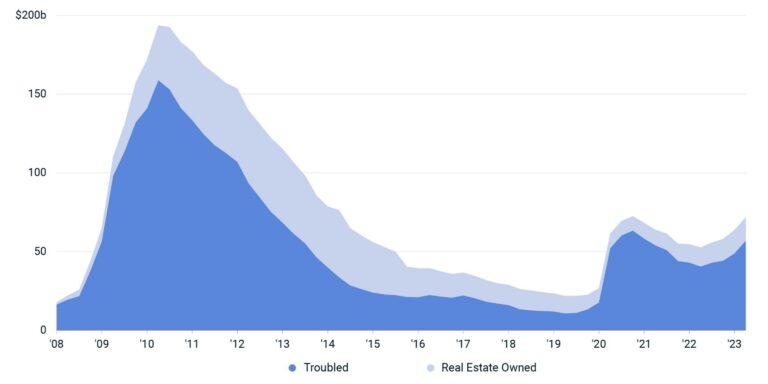

Data from MSCI Inc. indicates that the number of distressed properties has increased significantly during the past year. This graph shows the totals across all commercial real estate asset classes. (Chart courtesy of MSCI)

NEW YORK – Nearly $72 billion in U.S. commercial real estate (CRE) was considered “distressed” as of the end of the second quarter (Q2), an increase of 15 percent versus Q1, and another $162 billion of properties were considered to be in potential distress, primarily due to rising vacancy rates, higher debt costs or both.

The data cited above is from a report released July 19 by MSCI Real Assets, the investment analysis service of the New York-based finance company MSCI Inc., which considers distressed properties to include both financially troubled assets and assets taken back by lenders. The office sector had the most properties in financial trouble, accounting for $24.8 billion of the total. Retail properties were a close second with $22.7 billion of distressed properties, followed by hotels at $13.5 billion.

It’s no surprise that office buildings account for the largest dollar value of distressed properties. We’re all well aware of how the post-COVID-19 shift to remote work has adversely affected space demand, lease renewals and vacancy rates.

But properties across all asset classes – not only office – face another major challenge: more expensive debt. Low fixed-rate CRE loans are expiring and coming due for refinancing, but property owners are facing much higher interest rates and tighter credit. That “refinancing cliff” could lead to a wave of distressed properties, industry experts say.

But what about life sciences real estate (LSRE)? Life sciences properties with expiring loans presumably face the same refinancing challenges. Also, as BREI reported last week, some industry analysts say the office portions of office/lab buildings could be subject to the same remote work-driven vacancy issues as mainstream office space. As investment has declined, some life sciences companies have also reduced their existing space, curtailed leasing plans or both. And, of course, there are millions of feet of new space in the development pipelines of major life sciences markets nationwide.

Fortunately, the LSRE sector is not experiencing significant distress at this point, although that could change during the next couple of years, according to a group of industry executives who were part of a panel discussion during the IMN (Information Management Network) LSRE Forum, held June 28 in New York. The session was titled, “Investing in Real Estate for Life Sciences.” It was moderated by Christian Dalzell, founder and managing director, Dalzell Capital Partners LLC.

The panelists were:

■ Michael Borchetta, director, transactions, Harrison Street Real Estate Capital LLC;

■ Marci Loeber, managing principal and chief investment officer (CIO), Griffith Properties LLC; and

■ Tim Olivos, managing director and portfolio manager, Ventas Inc. (NYSE: VTR).

Last week, BREI shared the panelists’ comments on the LSRE investment market in general, their approach to underwriting, how they’re sourcing deals, where they’re finding opportunities, why tenants are being more selective, and how all of that is affecting leasing and asset values.

This week, we are focusing on their insights into distressed properties, as well as changing lab-to-office ratios, emerging geographic markets, the impact of AI (artificial intelligence) and other scientific breakthroughs, the persistence of the bid-ask gap, and more.

‘We haven’t seen distress yet’

With regard to distressed properties in the LSRE space, Mr. Dalzell asked, “Is it due to poor planning or construction or is it bad timing? And/or maybe even overcapitalization, or buying the wrong asset?”

“It’s kind of all the above,” Ms. Loeber replied, and it “depends upon the situation.”

Mr. Dalzell followed up, “Well, I guess I’m just trying to get a sense of how many new competitors are you guys seeing with the deluge of cash that has entered this market, which I imagine is rather difficult?”

“I think the reality is a lot of the supply is still delivering this year and going into the next year,” Mr. Borchetta said. “Pretty much every project that was delivered (in) 2022 or prior is full. I mean, the vacancy rates in some markets got as low as 2 to 3 percent. And so, in some ways, that really wasn’t a sign of a healthy market.

“I think we haven’t seen distress yet. The question’s going to be over the next 12 to 24 months,” he said, as millions of additional square feet of office and lab space are scheduled to be delivered in Greater Boston and other major LSRE markets.

“As that’s delivered, if the market from a leasing perspective stays where it is, that’s where you’re going to start to see potential distress,” he said. “But the reality is, from what we’re seeing right now, we’re not seeing significant distress in the space, which is certainly encouraging. And … time will tell how this … wave of supply coming online is absorbed…”

Referring to LSRE projects developed in suburban areas, well beyond the established life sciences districts, Ms. Lober added, “I think where you are starting to see some of the distress … is where people went farther out, right? It shouldn’t have been a life science (project), or someone that wasn’t in that space got in late and kind of got caught.

“So I do think, as far as new competition, you’re not going to see people come into this space right now because you can’t finance if you don’t have experience doing life science because of the unique nature of it. You’re not bankable. So that is a good thing from our standpoint. (There are) going to be less new competitors.”

Mr. Dalzell said, “Given every recession, or at least the many that I’ve been involved in, there always seems to be a litany of new lenders that pop into the void… I’ve heard of a few life science-focused debt funds that have popped up and newer debt funds. So I’m sure hopeful that (continues)”

“Absolutely. That would be wonderful.” Ms. Loeber agreed.

Changing lab-to-office ratios

Mr. Dalzell noted, “I don’t imagine that dealing with people who aren’t at the same level – the same level of expertise – that might make an unforced error, that doesn’t help you guys because, obviously, it’s a small sandbox. What do you think? Where do you see disruptors coming from for the environment for the life science sector in terms of its evolution?” He also asked about building flexibility.

“I think one of the things we’re starting to see is most groups have maintained a hybrid type of approach,” Mr. Borchetta replied. He noted that some life sciences firms are only requiring employees to be in the office perhaps three or four days a week.

“Obviously, there’s certain science you can’t do at home and so there’s a requirement for pretty much every person to be in the office at some point,” he observed. “But back-office support, etc., don’t need to be in five days a week,” which could alter the traditional 50-50 lab-to-office ratio.

“What I could see over time is a little bit more densifying on the lab side and right-sizing some of that general office piece,” he said. “So I think you could start to see a higher mix of lab overall. And then, separately, as companies start to advance and we’re onshoring more and more production, that GMP is all pretty heavy lab. And so I think that’s where you’re going to start to see a little bit more densification over time, within the tenant suites.”

“Yes, I think that’s right,” Mr. Olivos agreed. “I mean, we bought a portfolio in San Francisco very early on in COVID and, during the tour, we weren’t sure we are at the right building because only the scientists were in the building. So I think that probably is kind of how it’s going to evolve… Given the current hybrid approach, there aren’t as many people working in the office side.”

“And I think it’s, we were starting to see requirements are 70-30 (lab-to-office),” Ms. Loeber said, “and the challenge becomes that these buildings were not designed for that. In some instances, it’s 50-50 (or) 60-40. So that means a whole new capital investment on the landlord side to accommodate the 70-30 lab-to-office split.”

Mr. Dalzell asked why the ratio is changing.

“I mean, especially in the West Coast markets, that non-lab group does not want to come to the office, right?” Mr. Borchetta said, and they’re generally not required to be in the office full-time. “You do have these groups that … just don’t need as much space. You can come up with a hoteling solution or something else on that piece of it.”

Ms. Loeber added that many of her firm’s tenants are in the relatively early stages of raising venture capital, “Series A, Series B. So their boards are telling them to cut costs. And where can you do that? You can’t do it in the lab space. So you shrink your requirements… You can’t shrink your lab portion of it, but you can shrink your office.”

Emerging life sciences markets

Mr. Dalzell then asked which less-established geographic markets are emerging for life sciences.

Mr. Borchetta noted that the Greater Philadelphia market “saw positive net absorption in Q1 … that’s more absorption than some of the much larger primary markets. So that seems to be one that’s healthy. You obviously have great anchor institutions there, and so I think that’s one that’s going to continue to see attention.

“We’re also invested in both Boulder (Colo.) and Durham (N.C.),” he continued. “Each of those kind of have a little bit of convergence between tech and life science. Both are established hubs where Google’s put a meaningful presence there, as well as just life science innovation happening. So those are two other markets – obviously, anchored-by-university markets – that I think will continue to get more attention, and ones where several institutions now own today.”

“Yeah, I mean, we’ve talked about it. Universities are just a driving force,” Mr. Olivo said. “They provide the talent base. And if they’re trying to create an ecosystem to commercialize their research, it’s super important, and you’ll see it downstream in (what) we consider smaller markets.

For example, he said, “We’ve got relationships with (Washington University) in St. Louis, Duke in Durham, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. So those aren’t what you’d consider your like core life science markets, but you can make those markets work given the university partnership.”

“We also very much like suburban Philly,” Ms. Loeber said. “One of the reasons we like Philadelphia – the greater metro area – is the employee base. Big Pharma’s been there forever. So we’re focused more on single-story buildings that are adaptable for R&D, for GMP or medical device, and you have that optionality but you also have that employee base, which is critical.”

Mr. Dalzell then asked about the importance of speed-to-market.

“Certainly one of our strategies has been speed-to-market,” Ms. Loeber said, “because the duration to sort of go ground-up development can be so long you can miss a cycle for sure.”

Mr. Borchetta added, “There are specialized uses in spaces that need that.” In major markets, he said, when “these groups advance their science and need a spot to actually create their product, they’re not going to do that in a very expensive space in a market like South San Francisco or (University City in Philadelphia), where rents are through the roof and the space just isn’t accustomed to that.

“So going to a suburban market where there’s industrial-like product that can have a 24-foot clear (height), that can house warehouse space, can accommodate GMP, and also house some office or ancillary – they’re elusive uses. That’s where the opportunity is in some of these markets. So we’re seeing good demand in that segment.

“And I think Philly’s a great example of that where you have kind of the downtown R&D space really supporting the more suburban warehousing and manufacturing space.”

The next big breakthrough

Noting that advances in cell and gene therapy have given a huge boost to the life sciences and LSRE businesses in recent years, Mr. Dalzell asked the panelists if there are any other major scientific breakthroughs on the horizon.

“I think … what you’re seeing now is, with this AI push, there’s a ton of applications,” Mr. Borchetta said, noting that a recent survey found that 74 percent of VCs surveyed said they made at least one investment in AI or machine learning (ML) startups during the past 18 months,

“So, I think that ultimately helps San Francisco,” he said. “You’ve seen an outsized share of venture capital money go back into San Francisco, despite some of the challenges they’re having at a macro and city level there. So, that’s one.

“You combine that with Stanford and Berkeley and the National Lab there. I think that’s one where, in a couple of years, as these groups start to work through the initial kind of Series A money, that’ll be interesting to see if those companies play out. I think that could be kind of a re-acceleration of demand there.

Mr. Dalzell then asked the panelists what metrics they look at to assess the market.

“Well, part of it is we’re more bottom-up investors,” Ms. Loeber replied. “So we’re not big enough to do sort of a macro bet, which I think is what you’re driving at…”

“But it’s important to see which VCs are investing,” Mr. Olivos noted. “I mean, I think there are certain names that you want to follow. If they’re investing in those smaller tenants, that’s a pretty good sign, typically.”

“And inevitably some are going to fail, right?” Mr. Borchetta pointed out. “So, in these markets, the more you have the better.” He gave the example of properties developed by Baltimore-based Wexford Science & Technology.

“Going back to some of the Wexford properties, what you saw is, you might have started with five or 10 tenants that were 10,000 to 20,000 square feet, and inevitably a couple would fail. And you have a group like Spark Therapeutics and Penn that all of a sudden would need, you know, half a million square feet because they’d just continued to succeed.

“So, I think the more opportunities there, the more likely you are to have one of those companies really hit it in one of these markets.”

Mr. Dalzell asked about the importance of the management teams for life sciences companies. The panelists agreed that was important,

Ms. Loeber added that the management team is an important consideration, but so is which VCs are providing funding.

And regardless of the management team and funding, Mr. Olivos continued, “Like Michael said, some are going to fail, some are going to win. And it’s important to, hopefully, have the space to accommodate the winners. And … going in, you want to make sure your space can fit multiple tenants because there are going to be some losers over time. So you want to make sure you’re not having to spend a ton of T.I. (tenant improvements) to retrofit that space for the next tenant, because that’s going to hurt your bottom line.”

Mr. Dalzell asked how the panelists evaluate prospective tenants when they are smaller life sciences companies.

Mr. Borchetta said it is important to understand two things. One is the underlying strength of the geographic market. The other is understanding the science the firm is pursuing and how that relates to its real estate needs.

On the first point, he said, “If you’re leasing to a 10,000, 20,000 square foot Series A tenant in Palo Alto (Calif.), you have to be comfortable that Stanford’s going to produce another 10,000 to 20,000 square foot tenant out of their science … over the next couple of years and continue to feed that ecosystem. So I think that’s why you’ve seen such clustering… You’re a lot more comfortable investing in those markets overall.”

As for the second point, he said, “We always order kind of a management consulting report to understand what their science is… We aren’t scientists by background. We’re trying to understand from a real estate perspective, but it’s important to understand what they’re doing, what the likelihood is and how they’re how they’re approaching the business, so you can be better aligned with them overall.”

Ms. Loeber added, “We always talk to (the tenants). If need be, we talk to their ultimate investors.” In a market like Boston, she said, it is less risky to develop and lease speculative space because “we know that it’s reusable and it’s pretty generic.” But if a small tenant needs a lot of specialized TI, “they’ve got to have pretty strong financials because … the reusability of that space is critical, because you’re making a bet and a lot of them go out of business.”

The bid-ask gap persists

Mr. Dalzell asked if the slowdown in LSRE transactions for the past year or so continues to be due to a disconnect between the asking prices sellers are expecting and the prices buyers are willing to pay.

“Certainly, on the deals that have some sort of distress, for sure,” Ms. Loeber replied. However, she said, “On the stabilized deals, those cap rates are holding for the most part, with the exception of like ARE. People aren’t selling those types of deals because you do have the mark-to-market. Those cap rates sort of held despite the financing because people want that type of product. Institutions are focused on life science. So, if someone’s going to sell right now, then there will be buyers for it.

“On the distressed side, there’s certainly still some denial,” she continued. “But I think the good news on the life science side is, obviously, a lot of it’s demand-driven. But it’s not a question of if it’s going to come back, it’s when. Very different from the office dilemma and the demand there. So people just don’t know when it is going to come back… That’s why more institutional money is going into the stabilized (assets) – if you can get your hands on (them).

“And, I think the reality is, the market on the debt side – especially converted product or development products on spec – that’s where you’ve seen the biggest pullback right now,” Mr. Borchetta said. “There’s no bank financing available, which is more of a commentary on the risk profile than the asset class. And, similarly, the debt fund money is extremely expensive.

“I think the biggest change, today versus 12 or 24 months ago, is you’re getting significantly lower leverage and paying a significantly higher rate, both on the spread and the benchmark. So I think that’s where you’re going to start to see a real meaningful slowdown… When all those deals were getting done, and a ton of conversions and development projects were happening – you’re just not going to see that happen over the next 12 months or so, just where the debt markets are.

“So I think that’s probably healthy (because it) shuts off the supply line for the new supply. But that’s the biggest difference in terms of how we’re operating, or what we can and can’t do right now,” he said.

“And the deals are generally smaller than they were 12 months ago,” Mr. Olivos added, “It’s hard to make those pencil, those bigger deals. So a lot of people are looking at things unlevered and can take a bite that’s 100 million or smaller and make that work for their unlevered returns. So, try and avoid debt, if you can.”

Turning to questions from the audience, Mr. Dalzell asked which two or three life sciences markets will be top-of-mind for investors during the next could of years.

“I think we hit on a few, and I think of the primary markets that we talked about, San Diego does seem to be one that has the healthiest fundamentals. We’re continuing to see activity,” Mr. Borchetta said. “I think, one of the panelists earlier talked about Boston kind of being the first of this kind of slowdown in terms of demand. We saw that next in San Francisco, and we’re starting to see that a little bit in San Diego. But it does feel like one where you’re continuing to see meaningful activity, which is kind of in contrast, at least to those first two.”

“I think we’re … long-term bullish on all markets,” Mr. Olivos said. “I think there are pockets of every market that make sense as things retrench a little bit. But I think Philadelphia has come up a lot. We’re obviously bullish there, but I think some of these smaller markets with universities can really do well right now as demand goes there.”

“Again, all supply’s not created equal,” Mr. Borchetta said. “I think you’re going to see certain submarkets and certain pockets of types of supply start to see more of a slowdown than others.”

For example, he said, “The Bay Area, if you look at South San Francisco down to Burlingame, that’s seeing 4 to 5 million square feet of supply delivered, all targeting R&D uses. When you look into the East Bay, that’s more of a GMP and med device market. There’s a significantly less supply there and less supply delivering. So, I think you can start to see a divergence in some of these submarkets, especially in the primary markets.”

Tenants have become more selective

Mr. Dalzell asked if there is pent-up demand in any of the primary markets. The panelists seem to agree that is not the case, as evidenced by the substantial amount of sub-lease space being offered there.

Concerning sub-leased space, Mr. Borchetta added, “I think there was a time, when vacancy was 2 or 3 percent, most groups said, ‘Hey, I’m progressing. I know I’m going to need 40,000 square feet in a year or two years. I don’t know if that’s going to be there. So I may only need 20,000 square feet today, but let’s take down 40.’

“And so that behavior stopped. If you need 20, you take 20, and those groups that maybe overextended or planned for either science to progress faster or for kind of advanced hiring that they didn’t need, that’s where you’re seeing most of that sub-lease space.

“You see it most in Big Pharma, where people took whole buildings when they thought they needed it, and then saying, ‘Oh, actually, we don’t need this … We had this insurance policy when the market was really tight, but now, we don’t need it anymore.’”

Ms. Loeber noted that many life sciences firms are also unable to raise as much capital today as they could during the pandemic. So their space demands, which grew during the pandemic, have dropped back down to pre-COVID levels.

“Yeah, I’d say 12 months ago, when capital was easy to come by, you could go after five projects at the same time,” Mr. Olivos said. “But, now … liquidity is a little tighter and you have to pick the best one. So everyone is becoming a little more selective right now and you’re going to go after the best one of those five, not all five anymore.”

He noted that the same is true for VCs investing in life sciences companies.

“I think there’s less liquidity now, so it’s just more difficult to put money out,” he said. “So it’s no different than us looking at picking our favorite project; they’re having to pick their favorite companies…”

Mr. Borchetta added that some investors are shifting from pharmaceuticals companies, which are “a 10-year, $1 billion bet, which has now gotten exponentially more expensive with interest rates,” to lower-risk opportunities in the space, such as medical devices and biologics.

“I think you’re going to see a shift on a percentage basis more towards those and away from the pharma, just given those long, the 10-year process has become much more expensive with what cost of capital,” he said.

“And there was a euphoria during COVID with the investing,” Ms. Loeber added. “Now, people are taking much more time to understand the science as opposed to … just following the herd.”

Assuming that interest rates fall back to lower levels and financial markets stabilize, the panelists said they remain bullish regarding the long-term prospects for the life sciences industry and LSRE. They said part of that is driven by their expectation the additional innovations will continue to drive the business.

“It’s constantly evolving,” Mr. Olivos concluded. “I didn’t know what mRNA was before COVID.” ❏

The full content of this article is only available to paid subscribers. If you are an active subscriber, please log in. To subscribe, please click here: SUBSCRIBE